Recently, research has shed additional light on this relationship by indicating that the accumulation of dangerous proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease may be lessened by using a common sleeping drug.

The relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex illness with many underlying causes. But an increasing amount of studies is emphasizing how important sleep is for preserving brain function and maybe delaying the start of Alzheimer’s disease.

A considerable correlation has been discovered by researchers between sleep disruptions and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep disturbances frequently show up early on, before memory loss and cognitive deterioration become obvious.

This suggests that in order for the brain to carry out essential clearing procedures, sleep is essential. The brain helps eliminate trash while you sleep, including dangerous proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

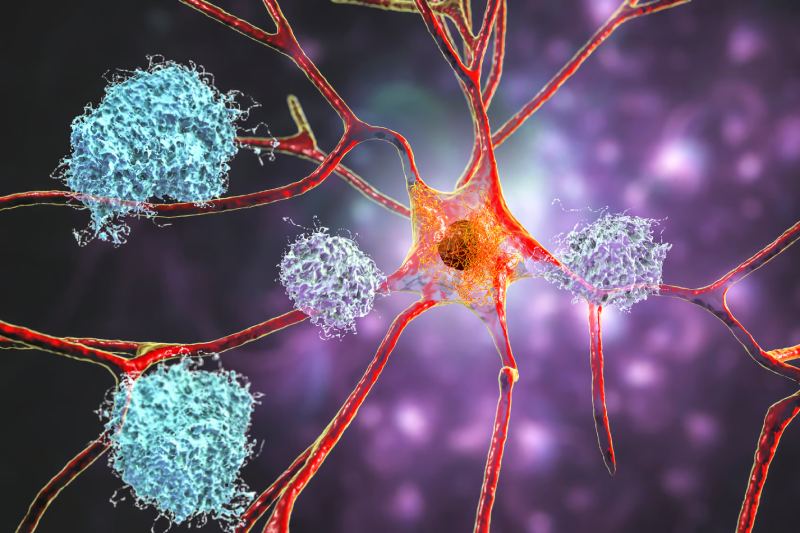

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the build-up of these aberrant proteins, mostly tau and amyloid-beta. These proteins have a propensity to group together to generate hazardous aggregates that impair regular brain activity.

Sleep disturbances impair the brain’s ability to clean itself. This permits toxic proteins to build up over time. The disease may arise as a result of the accumulation of these proteins.

Using sleeping drugs to treat Alzheimer’s

A new study by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis found that volunteers taking the popular medicine suvorexant for insomnia had slightly lower levels of tau and amyloid-beta proteins in their cerebrospinal fluid.

In addition to acting as a cushion for the brain and spinal cord, this fluid also helps the brain eliminate waste.

However, due to the limited sample size and short study duration, the findings are preliminary. In spite of this, the results suggest a potential relationship. Medication-assisted improved sleep may lessen the accumulation of dangerous proteins.

This is important because poisonous aggregates of tau and amyloid-beta proteins are formed. Alzheimer’s patients’ brains develop these clumps, which accelerates the disease’s course.

“If you can reduce tau phosphorylation, potentially there would be less tangle formation and less neuronal death,” says neurologist Brendan Lucey, who led the research.

Though he warns that we’re not quite there yet, he sees future research examining the long-term impact of sleeping medications on protein levels in older persons.

The brain’s nocturnal washing cycle

Sleep is an essential time for the upkeep and repair of the brain. The brain releases metabolic waste products that build up during alertness through a process known as the lymphatic system, which is triggered during sleep.

The proteins tau and amyloid-beta, which are linked to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, are included in this waste.

While he acknowledges that more research is needed, he hopes to one day examine the long-term impact of sleeping drugs on protein levels in older persons.

The nocturnal brain rinse cycle

Sleep is an essential time for the upkeep and repair of the brain. The brain releases metabolic waste products that build up during alertness through a process known as the lymphatic system, which is triggered during sleep.

The proteins tau and amyloid-beta, which are linked to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, are included in this waste.

Sleep ensures that potentially hazardous compounds be eliminated from the brain on a nightly basis. Sleep deprivation can disturb this process, leading to the accumulation of waste products, including proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease, which can exacerbate the illness’s course.

In addition, sleep issues brought on by Alzheimer’s disease may worsen, producing a negative feedback cycle. The illness worsens and disrupts the brain’s normal circadian rhythm, making it more difficult for the brain to eliminate these harmful proteins and causing additional sleep problems.

This vicious loop may hasten the disease’s course by hastening the buildup of dangerous chemicals.

A warning

The catch is that this study only included healthy adults without sleep issues, and the results were only shown over two nights, so don’t go running out to stock up on sleeping tablets. Whether sleeping tablets could be a long-term treatment or preventive measure for Alzheimer’s disease is still up for debate.

The hazards associated with long-term sleeping medication use include reliance and shorter sleep, which may, ironically, exacerbate the protein buildup.

“Those who are concerned about Alzheimer’s disease would be unwise to use this as justification to begin taking suvorexant every night,” cautions Lucey.

Reevaluating Alzheimer’s

This study also emphasizes how our knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease is changing. Reactions against the prevalent idea, which holds that aberrant protein clumps are the main cause, have been observed lately. After decades of research aimed at treating amyloid-beta, scientists are now having to reconsider their strategy.

It’s still unclear if sleeping medications can effectively prevent Alzheimer’s. Nonetheless, the study emphasizes how important sleep is for preserving brain function. Maintaining appropriate sleep hygiene is crucial.

For the safety of the brain, sleep problems like sleep apnea must be treated. Regardless of age, everyone should take these precautions.

Lucey has optimism that medications that utilize the connection between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease would one day be developed to halt cognitive deterioration. However, he notes, “We’re not quite there yet” for the time being.

Thus, as you drift off to sleep tonight, keep in mind that your brain is working hard to tidy up. Additionally, getting a good night’s sleep is unquestionably a significant tool for maintaining the health and happiness of your brain—even though sleeping pills might not be the answer to Alzheimer’s.

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology3 hours ago

Diabetology3 hours ago