Lawrence Steinman figures he might find out about baseball measurements than nervous system science – – and that is an accomplishment, taking into account he’s been a nervous system specialist for north of 43 years. As a baseball lover, he strikingly tuned in from a stereo as Lou Gehrig, a cherished New York Yankee player who had created amyotrophic horizontal sclerosis (ALS), conveyed his profound “Most fortunate Man” discourse before a pressed arena in 1939, where he expressed gratitude toward fans, family and colleagues for their help as his vocation was stopped.

“I may have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for,” said Gehrig.

Two years later, at the age of 37, Gehrig would pass away from the fatal motor neuron disease, which causes progressive paralysis. It also took his name, and ALS became synonymous with Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Steinman, MD, a Stanford Medicine professor of neurology and neurological sciences, pediatrics, and genetics, stated, “It’s one of the worst diseases.” Steinman and other ALS specialists are limited in their ability to assist patients as they gradually lose motor control and have difficulty walking, chewing, and speaking due to the lack of effective treatments.

Steinman stated, “The treatments work a little, which is better than nothing,” but he knows better than anyone that it is far from adequate. It explains why he is applying the lessons he learned from a successful MS study he led in the early 1990s in the hope that it will lead to a drug therapy that is similar for ALS patients.

Steinman and his colleagues as of late recognized a particle that could be focused on by drug engineers to treat ALS. The protein, alpha 5 integrin, is connected with another integrin (alpha 4), a kind of protein that helps safe cells move and tie to their environmental elements like Velcro. It was discovered to be a drug target for MS by Steinman’s lab. MS is a neurodegenerative disease in which immune cells eat the protective covering that surrounds neurons.

That examination prompted one of the main medication medicines for MS, which eases back patients’ side effect movement by restricting to alpha 4 integrin to hinder safe cell development and reduction irritation. Because ALS and MS both result in neuron death, possibly as a result of inflammation, the researchers believe that this novel treatment could have similar beneficial effects. On July 31, they published their work adapting the procedure for ALS in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The fact that anti-integrin therapy has worked in other diseases makes me think it’s really worth a shot in ALS,” said Steinman.

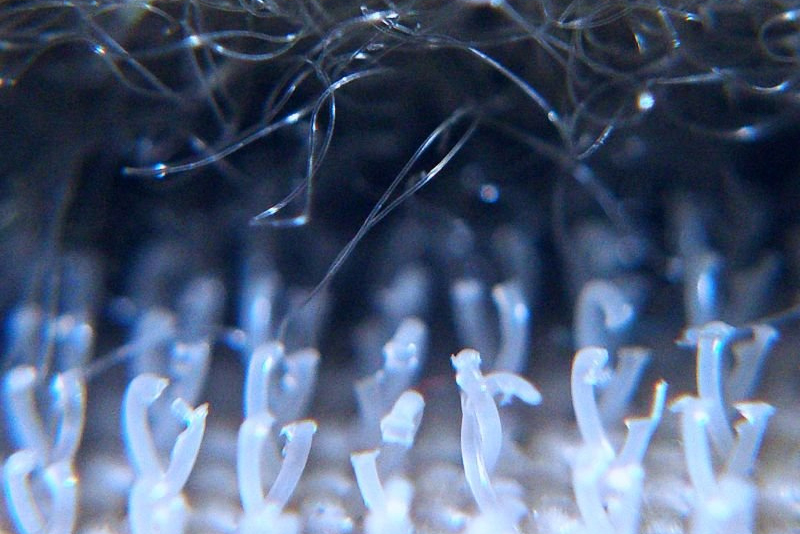

The expression of alpha 5 integrin in immune cells of genetically engineered mice with ALS-like symptoms led Steinman’s lab to believe that the protein, which helps cells bind to their surroundings in the body, was a contributing factor in the development of ALS. As the mice showed more symptoms that were similar to ALS, their immune cells had higher levels of alpha 5 integrin. Steinman realize that maverick resistant cells in the cerebrum and body assault engine neurons during ALS, making the phones shrink and bite the dust, and he was interested if alpha 5 integrin could some way or another be behind that cycle.

“We wondered if alpha 5 integrin might help immune cells eat motor neurons,” said Steinman.

Patients with ALS lose neurons in specific motor pathways, but their sensory pathways remain intact. In human examination tissue, this seems to be “pit like designs in regions where there used to be engine neurons,” Steinman said.

He asked his colleagues at the Mayo Clinic to investigate the locations of alpha 5 integrin proteins in autopsy tissue samples from 132 ALS patients. Steinman’s collaborators found more alpha 5 integrin in motor pathways from the brain and spinal cord of ALS patients of various demographics, treatment plans, and disease types when staining human tissue with certain dyes than they did in patients without ALS. They likewise saw that alpha 5 integrin specifically waited in engine pathways, yet not tangible pathways in ALS patient tissue.

“It was absolutely stunning,” said Steinman. “Alpha 5 integrin is only where the motor neurons are and in the tracts that carry the motor nerves. In other words, alpha 5 integrin is only where the disease is.”

Steinman’s colleagues likewise showed that degrees of safe cells containing alpha 5 integrin were higher close to harmed engine neurons in the cerebrums of perished ALS patients.

Steinman wanted to know if a drug that blocks alpha 5 integrin could help with ALS symptoms in mouse models. His group discovered that the drug, which binds to the integrin, improved motor function by possibly preventing their immune cells from moving and engulfing motor neurons.

“That was thrilling” Steinman said, “Seeing the night and day difference in mice, I thought, ‘This could be the anti-integrin drug that works against a horrible disease.'”

Since the drug largely fails to cross the blood-brain barrier, it only targets alpha 5 integrin in immune cells in the brain or spinal cord in trace amounts. However, it may be able to reach other immune cells throughout the body, thereby reducing inflammation and safeguarding motor nerves outside of the spine, both of which may halt the progression of the disease. Steinman hopes that his team can assist in the development of a drug version that can more successfully cross the blood-brain barrier, thereby preventing motor neuron death in the brain and possibly halting disease progression.

In any case, the medication in its ongoing structure could hold guarantee for people, Steinman said, and he and associates are pursuing following stages to test it in clinical preliminaries.

“With this research, we finally reached first base, and we’re actually running pretty fast to try to move this to second base,” Steinman said. “We might get disappointed. But on the other hand, I’ve seen things like this work amazingly well.”

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology2 weeks ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago