The dozens of subtypes of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy are hard to tell apart; a genetic muscle disease that affects only a few people and causes weakness in the hips and shoulders, making it hard to walk and lift one’s arms. Due to the lack of specific treatments, determining the subtype has not been crucial to patient care up until this point. However, due to the fact that gene therapies are on the horizon and are focused on specific genetic variants, determining the genetic causes of each patient’s disease has taken on a new significance.

In new research, a team at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has developed a methodology that could be useful to doctors make more precise diagnoses. The study will appear in The Journal of Clinical Investigation on June 15.

There is a connection between limb-girdle muscular dystrophy and hundreds of genes. Although each patient with the condition may have a few rare genetic variants that can be identified through genetic testing, it is impossible to determine which variant, if any, is responsible for a patient’s symptoms without lengthy and laborious additional tests. Unfortunately, there is currently no comprehensive list of all the variants of the genes that are associated with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, as well as information regarding whether or not each variant can cause the disease.

At Barnes-Jewish Hospital, Weihl treats patients with muscular dystrophy and serves as chief of the neuromuscular diseases section.

“These patients are in limbo. We can’t get them into clinical trials until they have a diagnosis. More than half of all patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy are in this position. It’s critical that we resolve their diagnoses so we can get them access to necessary therapies as soon as they become available.”

A significant step has been taken by Weihl and his Washington University colleagues toward the creation of a catalog that may assist in resolving ambiguous diagnoses. The protein that would be made from the instructions of one gene that is frequently involved in the disease was developed by the researchers. After that, they created each and every protein variant that could be made by substituting one amino acid for another, looked at how the variants worked and then categorized each variant as harmful or benign. Now, if a patient has a variant of this one gene, doctors can simply look it up in the catalog to determine whether or not it is pathogenic. In theory, the same method could be used to resolve variants of unknown significance for many other genes associated with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, greatly simplifying and expediting the diagnosis of this complicated condition.

According to corresponding author Gabriel Haller, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurosurgery, “People conflate knowing that there is a variant with knowing the cause of a disease. That isn’t necessarily the case. In this study, most of the variants of unknown significance turned out to be benign. If you find a variant but you don’t know its significance, you haven’t figured out the answer.”

Members of underrepresented groups particularly benefit from resolving variants of unknown significance. The genetic diversity of the western European population is reflected in the dominance of Western Europeans in genetic databases. The term “variant of unknown significance” refers to genetic variants that have no match in reference databases and are more common in people from other backgrounds.

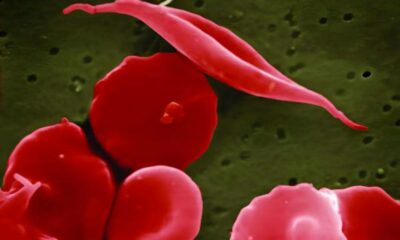

Sarcoglycan beta, one of the genes most frequently linked to limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, was thoroughly examined for this study. On the surface of muscle cells, sarcoglycan beta joins forces with three other proteins to form a complex. The complex needs to form correctly and be in the right place on the cell for muscles to contract effectively. All 6,340 sarcoglycan beta protein variants were created by first author Chengcheng Li, Ph.D., a staff scientist in Weihl’s lab. She then used a fluorescent antibody to determine where each variant protein was on muscle cells. Variants that are capable of forming the appropriate complex at the appropriate location -; that is, variants that exhibit normal functional activity brightly fluoresced. Those who did not form the complex correctly or were positioned incorrectly -; i.e., variants that are less useful -; fluoresced less brightly.

The connection was flawless. Functional activity scores were low for all known disease-causing variants and high for all known benign variants. In addition, functional activity level was correlated with disease severity. People who have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy with the most severe symptoms may require wheelchair use as early as age 7, whereas people who have milder symptoms may not require one until decades, if ever. In the study, patients with more severe symptoms were more likely to have variants with lower functional activity.

“Twenty percent of the variants of unknown significance turned out to be pathogenic, which means they could be amenable to potential therapies,” Weihl said. “My dream is that one day we’ll be able to give people a genetic test report that says, ‘You have this variant, and it’s amenable to this type of therapy,’ and we can start them on the best therapy right away. Or we tell them, ‘Your variant is benign,’ and we keep looking until we find the variant that is responsible for the patient’s disease.”

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology7 days ago

Diabetology7 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology1 week ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology5 days ago

Diabetology3 days ago

Diabetology3 days ago

Diabetology3 days ago

Diabetology3 days ago